Set at the turn of the 20th century, and unfolding over a single day in 1902, Daughters of the Dust (1991) explores the anxieties and aspirations of the Peazant family on the eve of their migration north. Shot on location on Saint Helena Island as the family prepare for departure from the Ibo Landing, they each spend the day entangled in reflections upon their individual relationship to Gullah history, identity and future as they each decide whether to migrate, remain, or return to their ancestral home on the island.

This essay examines whether it is possible to circumscribe an individual, heterogenous self among the aesthetics of collectivity in Julie Dash’s Daughters. By “aesthetics of collectivity,” I refer to Dash’s privileging of wide, communal shots and shared frames – Figure 1 and Figure 2, for example – in addition to the absence of both a singular protagonist and a linear narrative.

Figures 1-2

Constructing an intricately pluralistic film that engages with diverse voices and personal truths, Dash takes care not to depict any one character as central or as embodying a perspective that is esteemed over the beliefs of others. The result is a film without a centre against which to verify alternate representations of truth, signalling a departure from hegemonic conventions in Western cinema, where a central figure tends to allow for passive spectatorship through objective storytelling.

This implicates the identity of the Peazant family as multi-layered and contingent on their ancestry, collective memory and traditions of oral storytelling and folklore. Exploring Daughters’ potent imaging of gaze, water, and non-linearity, I will examine the extent to which the film creates potential for the characters to inhabit a discrete selfhood, or whether the identity of the characters will always be predicated upon their shared name and ancestry, so that any sense of self is only understood as a refraction of the preceding and dominant collective identity.

In New U.S. Black Cinema, Clyde Taylor identifies an expanded focus of the camera within new black films – meaning works made in the late 60s to 80s by a group of filmmakers at UCLA, including Dash herself— making the lens “more open to diverse, competing, even accidental impressions” and capturing multiple meanings (Taylor). Arising from a dissatisfaction with the films produced in the dominant Hollywood film industry, these students, named “the L.A. Rebellion,” sought to “demand some work on the part of the spectator who has been conditioned by habits of viewing industry fare” (Bambara) to rely on an official and reliable story offered by a central protagonist, newly turning to honour multiple perspectives and contributing to “a Black-oriented cinema more grounded in Black aesthetic traditions.” (Field)

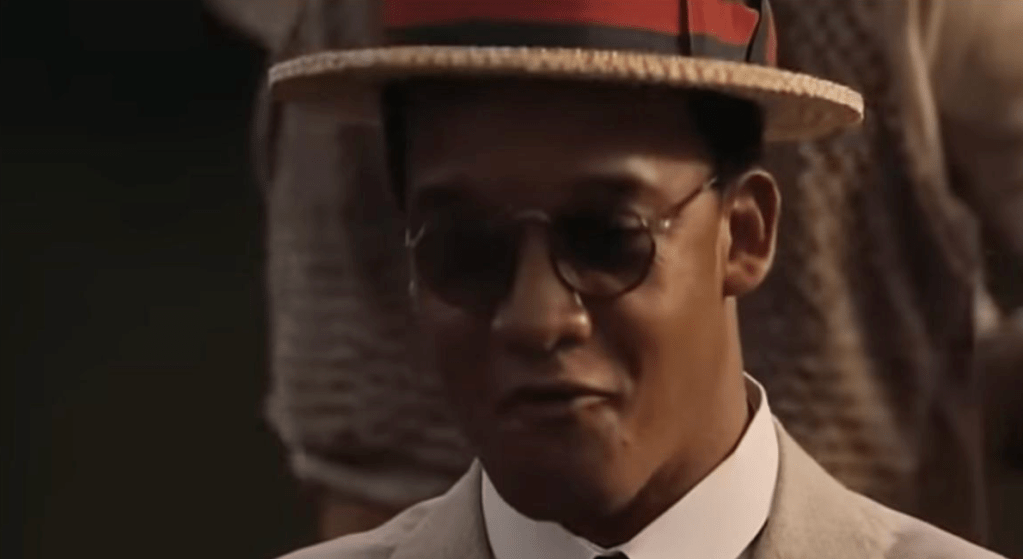

This endeavour to “widen the scope of Black film in an industry that spends itself to narrow it” (Hunt) is reflected in Daughters through the layered, intersecting and discursive perspectives, in addition to the theme of gaze introduced in the film’s expositional sequence. The presence of a kaleidoscope (Figure 3) instantly “signals that Daughters is a film about ways of seeing,” (Brouwer) including ways of demarcating individual identity in relation to a collective identity. Other props that contribute to the film’s overall mise en scène, including Yellow Mary’s veil (Figure 4) and Mr Snead’s sunglasses (Figure 5) and camera, continue the renegotiations around gaze. Ways of seeing problematise possibilities for a distinct selfhood in the film, as the subjectivities of cinematographer Arthur Jafa’s camera are invoked through Mr Snead’s camera. At first an “in-between character,” (Bambara) he becomes an anthropologist immersed in the Peazant family’s histories and finds that his camera cannot compress their livelihoods into a singular frame.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

A close-up first introduces Yellow Mary, her face obscured by a white veil while her collar is embroidered in criss-cross detail (Figure 6), suggesting a dual identity in conflict. Flowers encircle her hat, juxtaposing natural elements of beauty with the fashioned garment she wears, and its white brim partly conceals her gaze. In the same sequence, Viola and Mr Snead are introduced at a low angle in a POV shot from the boat (Figure 7). Any sense of ideological superiority suggested by the actor proxemics is subtly undermined by the shaky handheld camera, foretelling that the security of their identity built upon pursuing “progress” is shaky and will face a trial during the family reunion. When they board the boat, the camera oscillates between Viola beside Mr Snead/Yellow Mary beside Trula, in shot-reverse-shot, introducing two oppositional modes of “blackness—explicated, defined and constructed in relation to the gaze” (Hartman) — in a manner that is quite distinct to the rest of the film, where the camera tends to favour wide shots that underline collectivity.

Figure 6

Figure 7

A following extreme close-up through a kaleidoscope fills the frame and Mr Snead imparts a scientific and etymological dissection of the object. Simultaneously, the women marvel at the beauty of the object without explicitly acknowledging his explanation, implying that their fascination with it doesn’t hinge on understanding its mechanisms. Seeking to “know” can translate to seeking to dominate through the “mental colonisation” (Taylor) of nature, so the women’s silence indicates a rejection, or quiet resistance, of this thought process, and a reclamation of the value that lies in beauty independent of rational or scientific explanation.

Spectators are invited to meditate on the reflecting surfaces within the kaleidoscope, tilted towards each other to reveal a symmetrical pattern due to repeated inflection, and its symbolic purposes in the film. Beyond an ostensible reading of the kaleidoscope as underscoring the multiple perspectives within Daughters, we are invited to consider the meaning of a reflection. Rather than a ‘pure’ reality, a reflection represents an inverted (distorted) and flattened image of the self, that draws near to the real, embodied self, but cannot be exactly equated to it. Similarly, we can read that Dash approximates Gullah identities in a mode akin to “speculative fiction,” (Gourdine) where the film functions as a bridge reconnecting audiences with history reflectively rather than biographically.

After this, Mr Snead is shot wearing sunglasses. As an accessory of modernity, these tie him to Viola, newly Christianised, helping us to greater understand the pairing. Both “the veil and sunglasses aim to disrupt gazes,” (Botz-Bornstein) and each conceal different parts of the face, but their dissonant functions implicate the identities of the wearers. A veil allows Yellow Mary to become a spectator without being gazed at, suggesting that Dash does not intend to distort the characters to lend an ‘easy reading’ of the film to white audiences, as Yellow Mary “does not offer herself to be looked at.” (Botz-Bornstein) Sunglasses also enact a selective covering of the face: similarly used to “deflect the gaze of others without causing conflict,” (Botz-Bornstein) yet remaining distinctly grounded in aesthetics of coolness developed as “an extension of the instinct to survive.” (Mayors) As a photographer, Mr Snead is a character on the edge of the Peazant family. The sunglasses thereby typify him as a figure gazing from the peripheries, inviting a reading of him as a man interested by driving progress as much as Viola, insofar as he is engaged with matters of science and with self-fashioning himself towards a future in actioned autonomy.

Both accessories are united through characteristics of “presence and non-presence, creating the effect of mystification” (Botz-Bernstein) in relation to self-presentation. Lending a disembodied quality, this underscores the challenges with demarcating any discrete selves within the film, as characters engage in “self-writing through dress,” (Gourdine) which unites them through rituals of reclaiming autonomy, such as conceptualising the self within the lines of fashion. Though they each seek to (re)construct a self, more dominant is the alignment in their shared attempt, uniting them through daily resistance.

Presence and non-presence are further entangled in the reciprocally-informing voices of the two narrators—Nana, the family matriarch, and the Unborn Child. While the Unborn Child is not yet alive, her presence is haptically felt through kinetic and aural associations with the wind. Nana, on the other hand, is on the precipice of becoming bound to memory in the minds of those who choose to leave the island, often framed close to the soil which ties her to moribundity. The Unborn Child has been shaped ineffably by the past and in the same mode, Nana informs the future, reflecting a merging of personal history as blending together “with the history of all women, as well as national and world history,” (Cixous) which locates the self (as woman) as a palimpsest of interrelating realities. Nana echoes “I am the honoured and the scorned one […] and many are my daughters.”

The stilling of the flux of time and space allows for the eldest and youngest of the Peazant family to inhabit liminal roles which are negotiated through the representation of water—a motif which proliferates throughout Daughters. Diverse bodies of water are filmed in dialogue: the water Bilal faces to pray (Figure 8), the lake Nana bathes in, the river facilitating the canoe trip, and the ocean as backdrop to farewells.

Figure 8

Bodies of water in bondage are explored in the first sequence of Nana bathing (Figure 9), dissolving into close-ups of the interiors of Eli and Eula’s bedroom, where white gauze veils their bed (Figure 10), symbolising sanctity of marriage and placing it in dialogue with Yellow Mary’s similar costuming, thereby relating the two women to one another. This pairing is explored as another doubling or mirroring (such as Viola and Mr Snead, or Nana and the Unborn Child) that facilitates closer character analysis when filmically united as a pair. For example, we learn simultaneously of the Unborn Child’s prescience and Nana’s ancient wisdom— the two meeting in the circularity of time as they are the characters closest to the immaterial realm of ancestors. We then come to understand Eula similarly, in relation to the model of “scorned femininity” typified by Yellow Mary. It is through Eula’s impassioned pleading for Yellow Mary’s acceptance into the family that we understand Eula through her identification with Yellow Mary’s rejection.

Figure 9

Figure 10

In the same way, Nana and the Unborn Child’s presence underlie the entirety of the film, and as symbols of the past and future (not represented as oppositional directions but as reciprocal channels), they similarly challenge the notion of a self that can be fully understood in its singularity as they represent oppositional times borne from the present moment, neither existing without the other. This is emphasised through Nana’s assertion, “we will always live this double life you know, because we are from the sea.”

The pairings also mirror the camera’s attention to the bodies of water that render the islands a space of transatlantic memory and layered histories: a line of thought informed by the work of Astrida Neimanis. The canoe ride and the shoreline are perhaps the most dominant locations in the film, inviting audiences to recognise the diverse waterways encircling the island, mirroring the branched identities of the family which derive from a shared ancestral beginning. This underscores the guiding power of water for the Peazant family. To guide a child, such as Eula’s unborn child, “from potentiality to actuality [so] plurality proliferates,” (Neimanis) thus identifies the life-giving and sustaining potential of water, synonymous with Nana’s deific perception of her ancestors, where she can “catch a glimpse of the eternal.” (Wardi)

Like the intersecting voices in the film, the multiple sites of water upon which the film is built, each symbolise contrasting identities, yet also share material existence and the ebb and flow of histories contained in one rolling wave of film.

The bodies of water can also be understood as “metaphysical locations,” (Wardi) redefining peripheries, following African belief in “the realm of the dead located in the river bottom,” (Wardi) and Nana’s recurrent speeches about ancestors which unite the water with merging temporalities and co-existing realities. Differing tales of arrival onto the island further convey the dichotomous beliefs amongst the Peazant family and the potential for the co-existence of multiple truths, such as the oppositional retellings by Eula and Bilal regarding whether their ancestors walked on water or chose to drown. This reconfigures the sea as both a site of hope, life and home or a site of death –- in both cases defying easy classification but embodying both life and death, and thus, the potentiality for rebirth and becoming, displayed hopefully through the various baptisms permeating the film.

Wide tracking shots and bird’s eye shots of the island and its vast watery terrains are interspersed throughout the film (Figure 11), steeped in ancestral history and represented as a site of becoming for the children, as “the dancing, the celebrating, the education of children, all occur communally and outdoors.” (Brouwer) All of this considered in unison suggests that there is no disparate self or central selfhood amongst the family. Even their differing beliefs, rather than affording them a unique identity aside from their family, instead unites them through identification as they renegotiate their identity with issues of race, home, progress and future, reflecting Cixous’ notion of the self as “product of conflicted and differential relations.” (Wilson)

Figure 11

Non-linearity and lyrical fragmentation in film form and narrative further problematise the idea of a distinct selfhood as without linearity, there is no overtly traceable marker of character development, such as a typical character arc; instead, characters revel in the “circular perception of time, a past, present and future that runs concurrently” (Hunt) and necessitates that their identity be placed in discourse with other materialities and histories on the shoreline.

Fragmentation occurs along multiple axes, including (but not exclusive to) the fragmentation of the family as some decide to depart and others decide to remain, and fragmentation in religious belief. Bilal’s character is particularly useful for close analysis of this. Defined as an outlier, he is referred to as “backwards” by family for his Islamic beliefs and practices, yet Dash consciously encircles Daughters in images of water and of Bilal in prayer at sunrise and sunset. The decision to punctuate the film with this character implicates representations of the individual in relation to spirituality.

Depicted in silhouette, his unique characteristics are flattened, and he becomes a cut-out figure void of individual qualities. Silhouette is employed at moments interspersed throughout the film, such as Nana’s body first being introduced in shadow, despite her voice in ephemeral “circulation.” (Hartman) Emphasis on silhouettes, which threaten that the body become “disembodied, a free-floating signifier,” (Maurice) released from boundaries and swaying like the white billowing dresses of the Peazant women, thus disengages from Western notions of the self as attached to physicality. Similarly, Bilal is depicted in dark clothing as opposed to the other men, who are also dressed in white (Figure 12), in a long shot that sees him walk alone in the opposite direction to the others, creating a mirrored inversion.

Figure 12

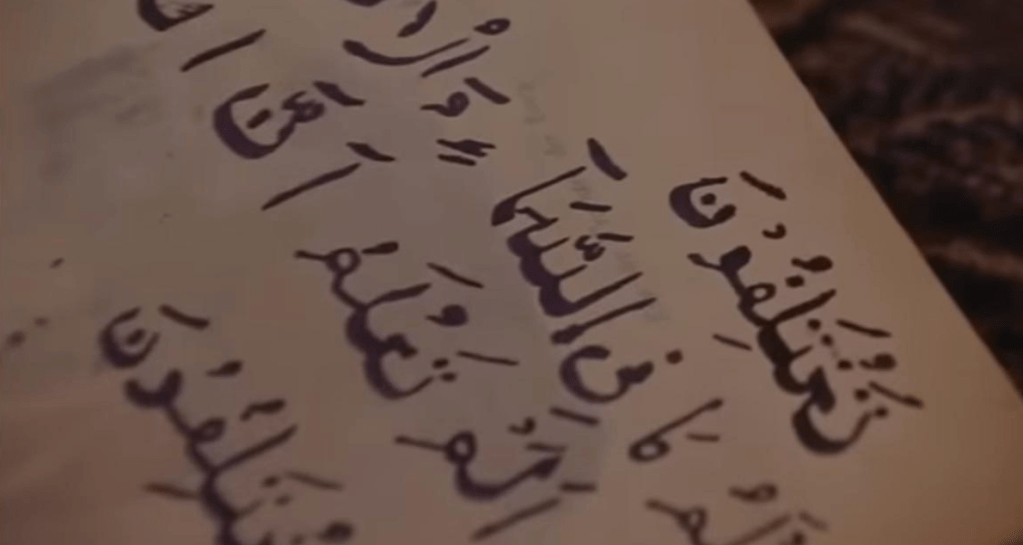

Through prostration, Bilal directs himself towards a telos of connectedness, extending far beyond discrete material conceptions of self. In Islamic prayer, there is a circularity to time – an alternate timeline easily distinguished from secular concepts of time. The Qur’an becomes coded as an important signifier in the film through close ups (Figure 13). The text aligns with the film along their shared temporal axis, as it also has a nonlinear format which is not seen to compromise its sanctity, but to accentuate it, “reflecting divine origins by destructing the spatio-temporal context and linear order of language,” (Gheitury) This further reflects Daughters’ successes as a non-linear work suffused with meaning, richness for interpretation, and a similar composition of (cinematic) verses, when compared to ayahs (revelations) in the Qur’an, echoing the film’s episodic and interwoven vignettes. They are further aligned through the similar origins in “deeply rooted oral tradition.” (Randeree) Furthermore, Islam maintains that the self exists, as much as it may function as part of a wider network, rather than demanding atonement for the self as steeped in sin, as in Christianity—represented by Viola. It instead seeks to return the self to the greater whole, a greater timeline beyond the linear limitations of the worldly dunya.

Figure 13

This echoes Nana’s conviction in her ancestors being alive within her body, and the compression of past, present and future into a singular moment of prayer – hands open in supplication drawing visual continuity with Nana’s open palms as dust gathers in and through them – functioning as a chrysalis of generational time. The snapshot and slowing of the frame rate facilitating communion of self with a realm beyond the material.

Perception of oneself through the eyes of others mirrors Dash’s interest in black identity in the gaze of the other, and reveals the binary oppositions or doubles that form a motif in her work. She refers to Du Bois’s “double consciousness,” to describe an inward “twoness” (Martin) that she is seeking to encircle in Daughters. Dickson suggests that the worst feature of double consciousness is that the doubled self rarely converges: “one prevails now, all buzz and din; the other prevails then, all infinitude and paradise.” (Dickson) However, perhaps they do converge in the reflective meeting-point of self-understanding through the other. This reading of Gullah identity as double or plural suggests that the self is not entirely absent but cannot be extracted from multiple ideological and temporal planes that coexist on the Sea Islands, presented through themes of gaze, water and non-linearity.

Dissolves, the collapse of distinct scenes within an already collapsed narrative, create the effect of suspending bodies as spectral and translucent in subsequent frames, so that presence is hinted at even in empty space, and the self becomes implicated in its environment, bound to haunt it and complicate boundaries of self and other. The permeable borders of the self reflected in the figuration of bodies where they don’t tend to be represented (Figure 14) exemplifies the challenges to identifying a discrete self in Daughters, particularly as the death evoked by these phantasms suggests “continuity of beings,” (Bataille) which posits a fluid self, mirrored in “images of water.” (Minh-ha) Bodies in silhouette and in shadow all point to presence through their absence but reinforce these reciprocal lines of relation rather than demarcating distinct selfhood, concluding that the self begins in reflection and discourse with water as first point of kin.

Figure 14

Bibliography

Bambara, Toni Cade. “Reading the Signs, Empowering the Eye: Daughters of the Dust and the Black Independent Cinema Movement.” In Black American Cinema. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Bataille,Georges. Eroticism. Marion Boyars Publishers, 2006.

Botz-Bornstein, Thorsten. “Veils and sunglasses.” In Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, Vol. 5. Routledge, 2013.

Brouwer, Joel R. “Repositioning Center and Margin in Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust.” In African American Review, Vol. 29, No. 1. Indiana State University, 1995.

Cixous, Hélène. “The Laugh of the Medusa.” In Signs, Vol. 1, No.4. The University of Chicago Press, 1976.

Dickson, D. Bruce Jr. “W.E.B. Du Bois and the Idea of Double Consciousness.” In American Literature, Vol. 64, No. 2. Duke University Press, 1992.

Field, Allyson Nadia. “Introduction: Emancipating the Image— The L.A. Rebellion of Black Filmmakers.” In L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema. University of California Press, 2015.

Gheitury, Amer. “The Qur’an as a Non-Linear Text: Rethinking Coherence.” In International Journal of Humanities, Vol. 15. Tarbiat Modares University Press, 2007.

Gourdine, Angeletta K.M. “Fashioning the Body [as] Politic in Julie Dash’s “Daughters of the Dust.” In African American Review, Vol. 38, No.3. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

Hartman, S.V. and Farah Jasmine Griffin. “Are You as Colored as That Negro?: The Politics of Being Seen in Julie Dash’s Illusions.” In African American Review, Volume 50, No. 4. John Hopkins University Press, 2017.

Hunt, A.E. “Without Living in the Folds of Our Wounds: A Conversation with Julie Dash.” In Notebook Interview on Mubi.com. 2020. https://mubi.com/en/notebook/posts/without-living-in-the-folds-of-our-wounds-a-conversation-with-julie-dash

Martin, Michael T. “I Do Exist”: From “Black Insurgent” to Negotiating the Hollywood Divide—A Conversation with Julie Dash.” In Cinema Journal, Issue 49, No.2. Michigan Publishing: 2010.

Maurice, Alice. “What the Shadow Knows: Race, Image and Meaning in Shadows (1922). In Cinema Journal, Vol. 47, Issue 3. Lawrence: Michigan Publishing, 1997.

Mayors, Richard, and Janet Mancini Billson. Cool Pose: The Dilemma of Black Manhood. New York: Lexington Press, 1992.

Minh-ha, Trinh T. Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989.

Neimanis, Astrida. “Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming A Body of Water,” in Undutiful Daughters: Mobilising Future Concepts, Bodies and Subjectivities in Feminist Thought and Practice. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Randeree, Kasım. “Oral and Written Traditions in the Preservation of the Authenticity of the Qur’an.” In The International Journal of the Book, Vol. 7, No.4. Common Ground Publishing, 2010.

Taylor, Clyde. “New U.S. Black Cinema,’ Jump Cut, no. 28, USA, 1983.

Wardi, Anissa Janine. “Daughters of the Dust and the Poetry of Water.” In Bodies of Water in African American Literature, Music, and Film. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2023.Wilson, Emma. “Identification and Melancholia: The Inner Cinema of Helene Cixous.” In “Paragraph, Vol. 23, No.3, Revisiting the Scene of Writing: New Readings of Cixous. Edinburgh University Press, 2000.

Leave a comment