An Interview by Jodie Foster

Hello Lucie, it is so nice to finally speak to you again – thank you for accepting to do this interview with Spotlight Magazine!

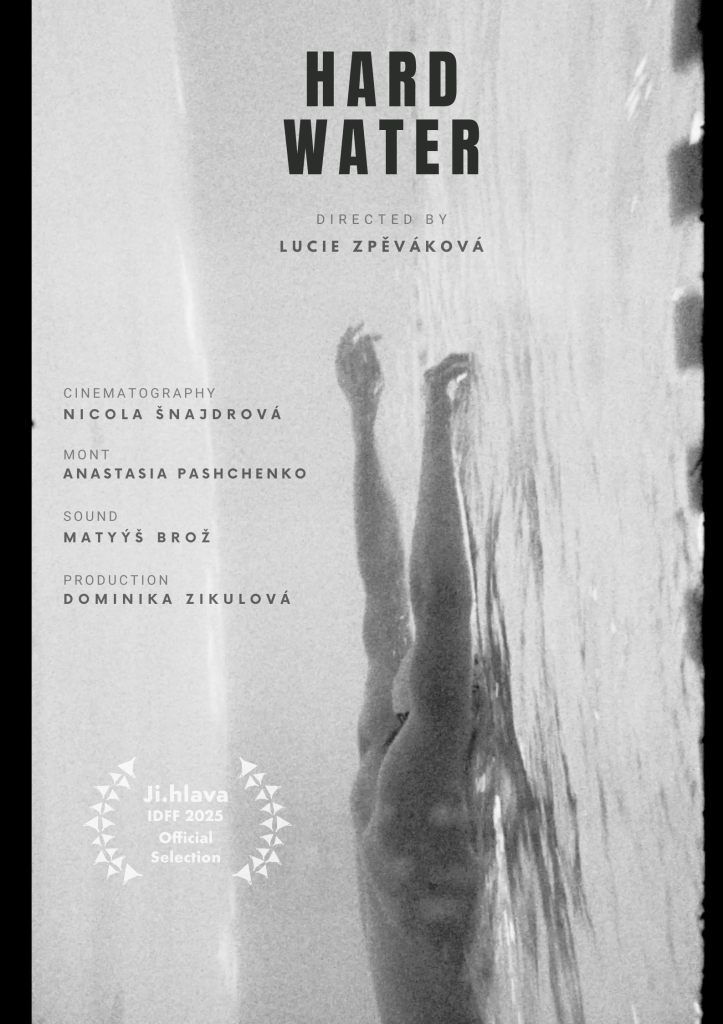

If I have done my research correctly, you have discovered your passion for cinema at a Summer Film School, and you’ve lived in the Czech Republic, Berlin, Argentina and England (where you attended the University of York)! I imagine all these cultures and landscapes are part of the reason why you got so interested in hearing and representing the stories of people, is that right? And now that you are a student at the department of Documentary Film at FAMU it all seems to have come full circle. I also heard that the short film you’ve chosen to talk about today was part of the Ji.hlava IDFF 2025 Official Selection, and that it premiered in November 2025. Congratulations on this achievement!

Now, let’s start with the title. I immediately thought that Hard Water sounded very evocative, and almost paradoxical. It brings together opposing ideas -something fluid and something resistant. Why did you choose this title in particular? What layers of meaning does it hold for you, and how do you see it resonating with the subject of the film?

[Lucie] The original title of the film was supposed to be Light of Water, which came more from my imagination of David’s relationship with water than from the reality I later discovered. Through observing and filming, I learned that water isn’t something deeply sensual for David, but rather a mechanical environment—one where he trains hard every day. I also wanted the title to highlight a certain paradox and the clash between our idea of water and David’s perception of it. The gentle water that guides him is also the place where he never rests, where he works intensely. The title also refers to a moment in the film when David says the first thing that comes to his mind is the coldness of the water—and whether it feels hard or soft.This literal description inspired us to choose a title that became a beautiful metaphor for both his training and his life.

That is so interesting, and it shows that our understanding of our own artistic creations may change along the way and that, if that happens, we need to let it happen. Actually, this film was made as part of a project under the brief of authorial reportage. How did you approach that category? Did you immediately think of this swimmer as the subject? Or were there other people or ideas that you considered before arriving here?

[Lucie] In the first year at FAMU, we create two final projects: one is A Reality That Matters to Me, where we have complete creative freedom, and the other is an authorial reportage, which serves as a contrast to the first exercise. In the reportage, we have to follow the rules of time and space, remain in one location, and give the film a more formal structure. In this case, I already knew back in October that I wanted to make a film about David, because I had listened to an interview with him and was fascinated by the idea of creating a visual medium that portrays the life of someone who perceives the world with all senses except visually. So from the beginning, I felt strongly drawn to this topic. Rather than presenting David as a Paralympic athlete who won Paralympics in Paris, I wanted to shape the reportage around perception through non-visual senses, and his relationship with water.

Wow, now that you mention in it this sort of meta-sensual commentary you were aiming for felt subtle yet very present in my watching experience of Hard Water. I imagine this must have been harder to achieve than it looks. When you first began planning the film, did you have a clear structure or visual idea in mind? How different is the final product from what you initially envisioned? And were there any major surprises in the process?

[Lucie] I started developing the idea in December, choosing my main focus and perspective. From the end of January until March, I began attending David’s training sessions to observe and build a sense of trust between us. Since David is a quite well-known figure in the Czech Republic, his family is very cautious about allowing journalists or media professionals into their private space. We agreed early on that we would not enter their private sphere, which helped us define the framework of the film strictly around the swimming pool and his training. We filmed in April and only had three sessions of two hours each. One of the biggest challenges was that we couldn’t interrupt the training or direct any scenes, as David was preparing for an important competition. That made the process truly documentary. The filming was fast-paced and entirely observational, relying heavily on our understanding of the training and the details we had already absorbed. As for the differences between the initial idea and the final result, there were definitely some. I always wanted the film to be minimalist and sensory, but the idea of building it around David’s counting only came during the editing phase, as did the inclusion of complete darkness. We had alternative versions that were almost silent, using only breath and counting. But eventually, we decided to include David’s voice. I wanted the audience to feel his energy and get a sense of his logical, rational perception of training rather than presenting a conceptual film that would only reflect the director’s and editor’s idealized view of reality.

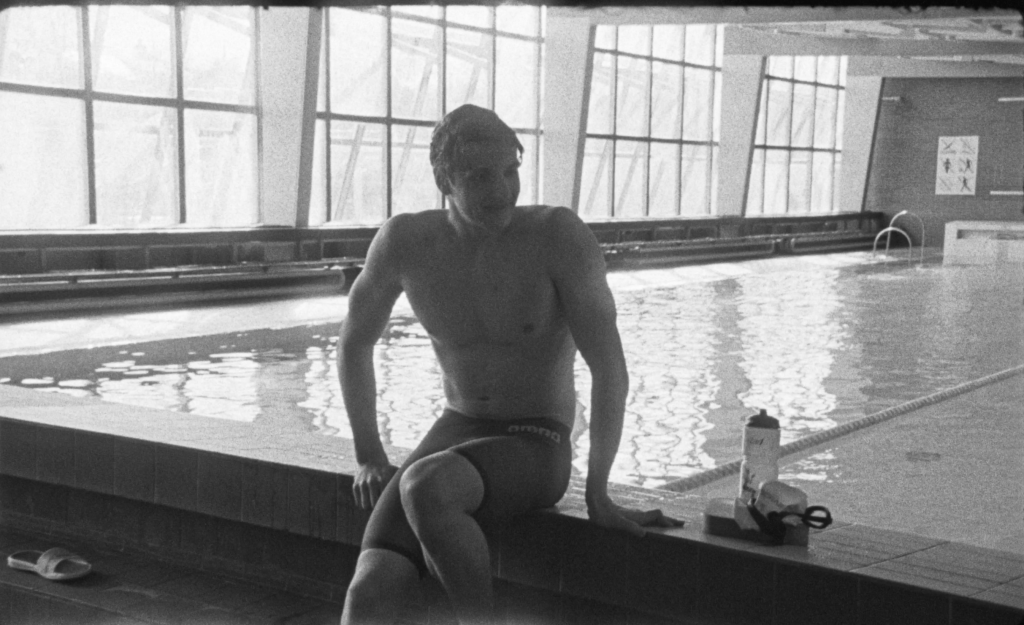

I understand, and I wonder if this documentary minimalism was part of the reason why you chose to film Hard Water in black and white. Can you talk us a bit through that choice? What did monochrome allow you to emphasise or remove? Did you find any creative limitations or advantages in working without colour?

[Lucie] Actually, filming in black and white was part of the assignment, since we were given 16mm film from the school. With color, you tend to focus less on structure and form, and in this case, I was very curious to shoot a black-and-white film underwater, especially since people always strongly associate water with blue. Blue already shapes a lot of the mood and energy for me, bringing peace, tranquility, and depth. Seeing the water in black and white, combined with the film grain, created a completely different world. Instead of swimming underwater, it looked like David was flying. Rather than focusing on the beautiful blue colour, the audience could focus on the movement and structure of the training.

Yeah, it’s true that there are so many standardised tropes and associations in contemporary cinema that filming it in blue might have almost felt misleading. But let’s talk about the start of the film now, for that is certainly one of the most memorable moments of the entire 7:16 minutes. At the beginning, David is seen touching the camera as if trying to understand it through his fingers. Why did you decide to open with that shot? What does it establish or evoke for the viewer?

[Lucie] During the shoot, I wanted David to understand what was happening, so we let him touch the camera and explore it so he could better imagine what we were doing. I asked our camera assistant to film it and keep the camera rolling, because I had this intuition that it could be very useful later. We decided to begin the film with this footage, as it is very surreal and sensory; it creates questions, but especially feelings, and brings us closer to David. It sets the tone for a film that is more exploratory and emotion-based rather than descriptive. We come back to this same footage at the end of the film, closing the circle.

Oh, that makes a lot of sense, and I’d dare say this particular intimacy and closeness will easily come across to anyone, even if the watcher may not consciously compute it. In fact, the image of him touching the camera feels almost metasensual. Film is a visual medium, and you show a subject who cannot see, but is trying to understand this visual instrument through touch. Were you consciously exploring this tension—between sight and touch, between the subject and the medium?

[Lucie] Yes, this was a conscious decision, and it wasn’t only this shot there were also other small details aiming to convey the tension between sight and touch, such as his feet touching the diving board before the jump, or the touch of his mom’s arm!

Wonderful, thank you. Another important theme throughout are numbers. They seem to take on a deeply physical and functional role for your subject—they’re not abstract, but embodied, used to navigate the water. You focus on the number sixteen. Is this a rhythm he created for himself? Or is it perhaps a reference to something like music, tempo, or stroke cycles?

[Lucie] The counting turned out to be the core of this short film, as it became a kind of compromise or connecting point between my idea of a very poetic film and David’s reality, which is rational, logical, and structured but not poetic at all. In my films, I don’t just want to present the topic only from my own perspective; I also want to draw from the energy of the characters which, in this case, was very different from mine. However, the numbers worked surprisingly well as a poetic, almost transcendental element that allowed us to get closer to David’s mind. At the same time, counting is something he naturally does while swimming to know when he’s approaching the end of the pool or to improve his focus.

Indeed, and this could even open a conversation on documentary as a genre, or documentary ethics, but let’s leave that topic for another time! Understanding David’s blindness is key to appreciating Hard Water, so let’s unpack this aspect a little bit. Throughout the film, there are subtle hints that the swimmer is blind, but you reserve a full close-up of his face until quite late, just after a black screen. First, we’re immersed in how he perceives the world, and only later do we see him through our own, visual lens. Was this ordering deliberate? A way to shift our perception, maybe even challenge it?

[Lucie] This was one of our biggest questions: When to reveal that David is blind? It even became a quite controversial topic among the audience at our school. Some argued that it needed to be clear right from the beginning, while others appreciated the slower process of picking up on hints and discovering it gradually. Despite trying different versions, my editor and I felt strongly about revealing it slowly and allowing the audience to piece it together. We didn’t want viewers to immediately label him as a “blind swimmer” and feel sorry for him. Instead, we wanted them to first see him as a dedicated, talented, and strong athlete and only then realise that he’s accomplishing all of this without sight. Rather than framing blindness as a limitation, we wanted to show how it gives him a different perspective and even advantages, as he himself says in the film. So yes, you noticed it correctly: the aim was to challenge, or at least shift, perception and above all, to give the audience space to question and discover.

That is incredible, seriously. It is precisely this type of challenge that drastically raises a film’s quality. Besides, audiences have become very complacent in their approach to film subjects, and they are quick to fall into a pitying mental space whenever a character lives in circumstances different from their own. That’s why I believe breaking down this kind of patronising attitude is absolutely worth the few minutes of confusion at the start of the film. But let us rewind the record a little and talk about the black screen I briefly mentioned earlier. This is a moment where the viewer’s attention is held entirely by the subtitles and sound. How important was sound in shaping this film? Did you rely mainly on diegetic sound captured during filming, or did you also introduce non-diegetic, perhaps “standardized” water sounds later? And what guided those choices?

[Lucie] In the dark part of the film, I wanted the audience to, for a moment, perceive the film in the same way as someone who is blind to show them how David experiences it, so we are on the same page. We wanted to give the audience space to dive into the water with David and stop seeing the film visually for a while. The sound our sound designer used in that part was a mix of recordings from the training sessions along with some non-diegetic sounds, created to work as 3D sound coming from all directions.

So it’s a matter of seeing by not seeing! Then what about after this moment? Immediately following the black screen, we’re brought back with a close-up of his face—this time in total silence, even removing natural ambient/diegetic sound. Was this choice designed to further heighten our awareness of visual dependence? Or what kind of effect were you hoping to create?

[Lucie] Initially, this moment was meant to be the point where we fully reveal that our protagonist is blind for those in the audience who hadn’t yet caught the hints and were still unsure or questioning it. But my amazing editor Nastya and I were aware of the emotional power of that moment, of the contrasting silence, and we instinctively knew that this was the right place for the close-up footage. We couldn’t fully explain why, we just felt it. We wanted the audience to find their own interpretation there or simply feel it. You found a beautiful message in the idea of visual dependence, so I guess keeping that moment was a good editing decision.

Sometimes the decisions that make the most sense are the ones that we feel instinctively, without necessarily understanding or justifying them through logic, and in this case it’s great that you listened to your artistic intuition. But can we talk a little bit about the underwater shots? I assume these were, unlike the previous “feeling”, a very concrete and logical decision. Did you use a different kind of camera or equipment to achieve those? And were there any technical or aesthetic challenges you had to overcome to get those sequences to feel as immersive as they do?

[Lucie] This was the most challenging part for our amazing production team, led by Dominika. We were using an old 16mm Aaton camera, which runs on a heavy battery that needs to be attached and carried by another person so filming underwater seemed almost impossible at first. However, I didn’t want to give up on the underwater shots, and neither did our absolutely incredible DOP Nicola, who came up with the idea of using an aquarium. So we borrowed an aquarium that was big enough for her to fit inside with the camera and battery. We added some weight to keep it stable, and then two camera assistants and I were in the water, pushing the aquarium and directing from inside the pool. It was completely crazy at one point, the whole swimming pool took a break just to watch and film us!

And that’s why creativity is so important in these scenarios! I’m sure it must have felt amazing to be able to film how you initially wanted and offset a medium obstacle with sheer originality. Now that we’re talking about your own creativity in tackling challenges on set, let me ask one final, all-encompassing question. Did filming Hard Water make you develop your directing skills? And what was the most important thing you learn while shooting this?

[Lucie] Oh yeah, that helped me a lot. This shoot really taught me how to work under pressure and with very limited time where you can’t always get the perfect shot, but have to go with what feels right in the moment. I learned how important it is to breathe, and to communicate both before shooting, to set the energy and flow, and during shooting, especially with the protagonist. I’m also a very intuitive person, so I learned that it’s okay to improvise and change plans simply because your intuition tells you to, even if you don’t have a rational explanation. I was very lucky and grateful to have such an amazing crew, and a strong relationship with my DOP, sound engineer, producer, and editor. We listened to each other, and our communication was smooth and full of empathy. We really considered everyone’s ideas and points of view. It was also about giving space to the DOP, to the editor, and showing trust in each other knowing that we’re all on the same level and that we all believe in the project. I realised how important it is to get along with your editor—because you end up spending hours and nights together in one room!

Perfect, thank you so much for your time and for all the thought-provoking answers! Looking forward to talk to you again, perhaps for a future collaboration with Spotlight? And best of luck with your career!

©Spotlight Magazine, Sun 4 January 2026

Leave a comment